|

| Quartz vein samples from Penn mines dumps containing visible gold recovered in 1981 (photo by Dan Hausel). All photos in this blog (except Google Earth images), were taken by the author. Feel free to use, but please give proper credit. |

In 1981, Wyoming experienced its first significant gold rush in the 20th century, following a release by the Wyoming Geological Survey of a report on gold assays of rock collected at Bradley Peak in the Seminoe Mountains (some vein samples ran as high as 2.87 opt Au, and one altered banded iron formation sample assayed 1.14 opt Au). Companies, prospectors, consulting geologists all wanted to investigate this area, but the rush was short lived.

|

| Years ago, at the entryway to the Bradley Peak Hilton - a home away from home |

After finding gold at Bradley Peak in the Seminoes, a few years later I met Dr. Terry Klein with the USGS. Over the next few years, our paths periodically intersected. Terry completed a PhD dissertation on the Seminoe Mountains and was the first to recognize komatiite meta-volcanics associated with this greenstone belt fragment, as well as a broad zone of propylitic alteration surrounding an area where I found some gold. This altered zone needed to be drilled and still remains mostly untouched.

This discovery of significant gold in the Seminoe Mountains was the first of a few gold rushes initiated by geologists with the Wyoming Geological Survey at the University of Wyoming. But this particular gold rush to the Seminoe Mountains was short-lived - not because of the lack of gold, but because of a lack of access. After receiving a copy of the report, one Wyoming company quickly flew the Seminoe Mountains dropping claim posts out of a helicopter blanketing the entire area in a short time. I was later told by company geologists that many posts hit the ground and bounced down the steep sides of Bradley Peak, while a few were caught in the tree top branches creating a whole, new, type of hazard for anyone walking through the trees during one of Wyoming's common and famous wind events. These are so common in Wyoming that Wyoming actually has wind festivals.

South Pass greenstone belt.

The Seminoes were a quiet place with no one around for miles. Basically, your nearest neighbor resides in Sinclair, 30 miles to the south. Personally, I loved working in the middle of no where. It grows on you to the point you periodically wonder if Ted Kaczynski was really all that crazy. I mean, the part about him living in the Montana mountains in a tiny, abandoned, one-room shack with no running water, sounds inviting; however, most people who do so either take up drinking, go crazy, or take up membership in the DNC.

So, here I was, living at the top of Bradley Peak and breaking rocks for breakfast, lunch and dinner. But a few odd things happened to me when I was up there. One event repeated itself periodically at night, and I never figured out what was going on. It also happened again when I was mapping at South Pass and in the Lewiston area, a few years earlier.

In the evening, I would climb into my sleeping bag with a gun and flashlight nearby. All of a sudden, I was startled awake by something running around my tent - very fast! I sat up and listened. It stopped. As I sat for a few more minutes, it started again - right next to my tent. What the heck? So, I slowly got out of my bag, turned on the flashlight and looked for a large rabbit, badger, fox, coyote, deer, zombie, or troll - I saw nothing. I stepped out of the tent searching for the critter - never saw it. This would happen periodically late at night. Based on the sound, I guess the mass of the critter was probably about that of a bobcat or mountain lion, but that was just a guess - I never saw the critter, nor could I find any tracks, nor can I think of what could run that fast around a tent in the dark.

|

| Recent conglomerate settling on top of false bedrock, Seminoe Mountains paleoplacer gold (photo by Dan Hausel) |

Another day, I met two of the nicest people anyone could imagine standing on my doorstep at the Bradley Peak Hilton: two rancher/prospectors of the highest quality - Charlie and Donna Kortes (God Bless them both). If you search a topographic map of the area, around the Seminoes, you will find geographic items in this region named after them, such as the Kortes Dam. Anyway, they just stopped by early one morning after hearing that I had moved into the area, and wanted to show me some rocks they found. So, we headed nearby to the Sunday Morning Prospect.

This was an old mine adit, not too far from my tent. After one crawls in the first few feet, the tunnel looks like it was offset by a fault (which it isn't), but for some reason, the miners who dug this decided to continue the mine tunnel about 6- to 7-feet lower, for no apparent reason. Maybe in was for some defensive position if they were ever attacked by bandits or marauding Indians. So to access the rest of the tunnel, one needed to find a way to get around this inconvenient drop in the floor. A small ladder would work.

Well, Charlie and Donna brought two, small, aluminum ladders and wired them together with chicken wire. As I climbed down the rickety ladder, Charlie announced he and Donna would sit outside the mine portal for their morning coffee break, to wait for me. E-gads! Are these two (who I had just met) going to sucker me into climbing into the mine, then pull the ladder out, steal my government 4-wheel drive truck with 200,000 miles of road wear, and leave me there to die while stealing my tent? I convinced myself that my tent was nice, but not that nice, so I continued into the mine. After a few hours, I worked my way back to the ladder, and - whew - they were still there. I climbed out of the portal and told them there was nothing much to see in the mine. But I did find a very nice specimen of massive cuprite with minor tenorite and malachite. If only there was more ore like this one.

|

| One of the first publications we released on the Seminoe Mountains. Co-authored with my good friend - Dr. Don Blackstone, Jr. (RIP). |

At the time, my research budget was minor. I was given a big job to map and find mineral deposits in Wyoming, and a research budget to pay for gas and cans of beans, so I had be use ingenuity. Luckily, one of my associates, a consulting geologist in Colorado, and one of the top diamond researchers from the former Soviet Union. I gave him some of the garnets and he sent them to a lab in Moscow for analysis: they turned out to be diamond-stability garnets (G10).

Because of extremism of communist regimes (think Brandon), Ed was now living in the US after being censored in the USSR (kind of reminds one of FB, Twitter, Linked-In and Brandon). One day, he had enough and applied to immigrate from the USSR - so, the communist courts placed him under house arrest for 5 years in which he had to somehow find food, etc. After the 5 years, they allowed his case to be heard, and he was thinking about looking for diamonds on a chain gang in Siberia. But, Ed had a PhD in geology (not that that mattered to the commies - remember the millions of the educated people including university professors, who were part of the government genocide statistics), and was one of the top researchers. So they gave him a break immediately pack and move to seek sanctuary in the US, or face a firing squad. He chose the former, and later co-authored a book on diamonds with me. Ed was not the only person who suffered this kind of treatment. I also had other colleagues thrown out of the USSR - one was a linguistics professor at UW, and the other a geologist who worked for me at UW. The professor was given a similar court verdict. After 5 years under house arrest, he moved to Wyoming. The geologist who worked for me, was shot at by East German guards, as he escaped over a barb wire fence to West Germany. So, this is where our country is headed right now!

Over the years I panned out numerous pyrope garnets from this paleoplacer. Every single pyrope our lab technician (Robert Gregory) tested with the electron microprobe at the University of Wyoming, had diamond-stability geochemistry! That had never happened before. Of all of the pyrope garnets I sampled elsewhere in the past, only a small percentage had diamond-stability geochemistry.

|

| The Bradley Peak Hilton - where I spent my summer vacation mapping the Seminoe Mountains greenstone belt. |

Over the years I panned out numerous pyrope garnets from this paleoplacer. Every single pyrope our lab technician (Robert Gregory) tested with the electron microprobe at the University of Wyoming, had diamond-stability geochemistry! That had never happened before. Of all of the pyrope garnets I sampled elsewhere in the past, only a small percentage had diamond-stability geochemistry.

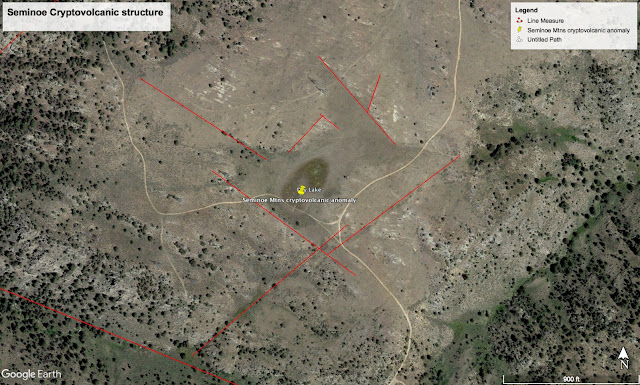

This data suggests there is one heck of a diamond deposit(s) hidden out there waiting to be discovered as well as some placer diamonds waiting to be found. In order to have those kinds of garnets scattered in the paleoplacer indicates the host diamond-bearing kimberlite pipe has been partially eroded and some diamonds from that hidden pipe could also be scattered in conglomerate on the north flank (and possibly south flank) of the Seminoe Mountains.

I could never get the director to request money from the legislature to search for the source of the gold and garnets in this region. But what the heck, directors often have better things to do - such as misusing state and federal funds, harassing geologists to death, and hiring communist Chinese and Russians (and yes, it did actually happen!

I could never get the director to request money from the legislature to search for the source of the gold and garnets in this region. But what the heck, directors often have better things to do - such as misusing state and federal funds, harassing geologists to death, and hiring communist Chinese and Russians (and yes, it did actually happen!

|

| Cryptovolcanic structure found in the eastern Seminoe Mountains - does this depression sit over a kimberlite pipe? Or is it just another intermittent pond? |

Well, I was still not finished with my interesting experiences. When you work in the Seminoe Mountains, one should think not only about gold, but also diamonds! When I mention diamonds in this sense, I mean diamondbacks!

I was working near Sunday Morning Creek on the North Flank of the Seminoe Mountains. It was very late in the day and time to get off the mountain. Being tired from walking all day my mind spoke to me - "watch for rattlesnakes" and just about that time, I stepped on a coiled rattlesnake! Have you ever seen a geologist in heavy hiking boots, a backpack full or rocks with a heavy utility belt break the world's high jump and long jump record combined? Years later, I mapped the Iron Mountain kimberlite district in the Laramie Mountains, I tried to break the record again and again!

Then, I should mention komatiite. I came across komatiites a long time ago on a diamond conference in Western Australia in some gold-rich greenstone belts. Komatiites are mafic to ultramafic volcanic rocks that one erupted directly from the earth's mantle when the earth's crust was very thin (more than 2.5 Ga). I found some in the South Pass greenstone belt after Dr. Terry Klein found others in the Seminoe Mountains. These rocks are important, not only to assist us in understanding geological evolution of the earth, but since they erupted directly from the mantle of the earth, they are often good source rocks for platinum-group metals, nickel, chromium and gold.

|

| Jasperized banded iron formation, Seminoe Mountains, WY (Photo by Dan Hausel) |

Well, I'll be a monkey's uncle! Originally, I sketched what I thought was a staff meeting.

But, I was wrong. Some years after I did this, someone pointed out not only the 2006 director of

the Wyoming Geological Survey, but there was also his buddy, the governor. So, maybe I

accidentally sketched the Wyoming DNC and didn't realize it - hey, is that Liz and Dick?

these are not from the Miracle Mile area, they are similar and include some distinct

purple garnets (pyrope) that are derived from the diamond stability field, some reddish to brownish

almandine garnets, some orange spessartine garnets, and emerald-green chromian diopside.

Like us on Facepuke, Twit and Linked-Out. Opps, never mind, our fact-checker determined these sites can't be trusted with facts or censorship. Therefore they are cancelled!

.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)